15th April 2020: How do we get out of Lockdown?

The novel coronavirus emerged through January, and within 3 short months has taken us into unprecedented territory. So unprecedented that Google Trends tells us that the word ‘unprecedented’ has been used 3 times more than usual in the first week of April! Today the world is in a situation that has never before been experienced. Not the pandemic – the world has gone through much bigger ones than this, it is the unprecedented response to the pandemic that takes us into new, unchartered territory.

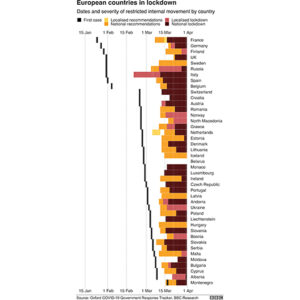

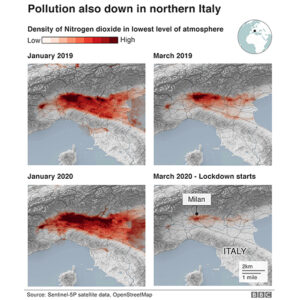

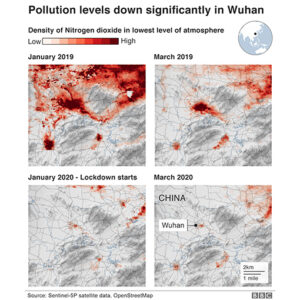

Back on 23rd January China announced the lockdown of Wuhan city’s 11 million citizens, to the astonishment of the rest of the world. Much was made of the fact that only an authoritarian regime could get away with demanding their population comply with such draconian restrictions. This was so much the prevailing thought that when the public-health and science experts put their first coronavirus control advice together for the UK and USA Governments, they barely looked at the option of a full lockdown because they believed it was not politically or socially an option. Later reports hurried to model the figures of a strong lockdown scenario, as it became clear that the virus was sweeping through Italy and beyond meaning the unthinkable lockdown was fast becoming the only viable option.

“Until that point, we weren’t even asked to model the idea of a total lockdown,” says Prof Edmunds. “It was only when Italy started to look totally horrific that those sorts of policy options suddenly opened up.”

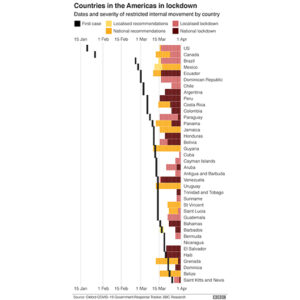

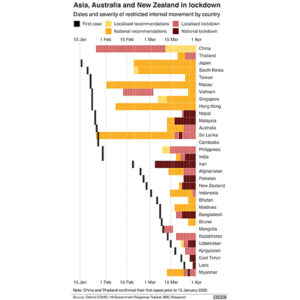

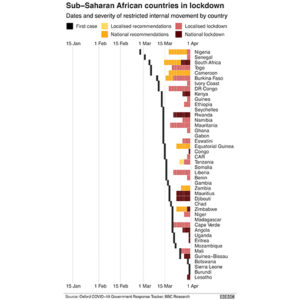

Unlike China, Italy decided, on 25th Feb, to put its whole population under quarantine – the first ever to do this. By the end of March over 100 countries had implemented either full or partial lockdowns. It is estimated that currently around 2.6 billion people are living under these restrictions (1.3 billion of these are India alone) – or approximately one-third of the human population according to Agence France-Presse.

No pandemic has ever before been handled this way throughout history. There is no past experience of whole population lockdown that can be looked to, learned from or compared against.

Even the term ‘lockdown’, which seems to have become the generally used word, has no real meaning. Past terminology was always ‘isolation’ to mean the separation of people who had caught a transmissible disease, or ‘quarantine’ to mean the separation of people who had been exposed, or suspected to have been exposed, to people suffering from a transmittable disease.

Thus the terms that exist cover the sick people themselves and those of their immediate family or contacts. There is no technical term for a pre-emptive segregation of entire populations to stop them from ever being exposed.

For anyone interested, the concept of quarantines probably first came about in Croatia in the 14th century, where the rule of trentino, a 30 day isolation of ships and crew, was imposed to prevent the bubonic plague being brought ashore. This idea spread and developed to 40 days, or quarantena – morphing to quarantine in English.

There is plenty of evidence of past isolations and quarantines that can be studied and learned from; the famous self quarantine of the UK village of Eyam during the Bubonic Plague in 1665, the huge efforts throughout Africa to control outbreaks of Ebola, the SARS and MERS epidemics, and smaller events like the quarantine of 7,000 Toronto citizens who were thought to had been exposed to SARS in 2003. All have been intently studied not just for the medical effectiveness, but also the social and mental health effects on people living through a disease outbreak and the control measures used. Learnings from past control measures were modelled into the forecasts and the suggested measures of our current coronavirus pandemic.

The belief that modern societies would not tolerate restrictions led to estimations being made regarding what level of compliance could be expected for each suggested intervention, with the spread of disease calculated against these estimated compliance levels. They judged the elderly were most likely to comply with requests to stay at home, so this was modelled in at an expected 75% compliance. Asking the whole population to practice social distancing was thought to be far less likely to be obeyed and was modelled in at 50% compliance.

These assumptions have been proved wrong; across almost all countries where lockdown has been ordered, citizens have heeded the advice. Compliance has actually proved to be far higher than the pessimistic modelling suggested, meaning the estimated death figures are likely to be less than first predicted. Which is one piece of good news at least.

However, the more successful the measures are at reducing the potential death rate, the more the public worldwide could begin to think that rather than the lack of deaths being because the changes of behaviour prevented deaths, that the low death rate is because the risk was exaggerated. This could lead to potential dissatisfaction or anger.

There is still quite a lot of surprise being expressed by social scientists over how submissive the public have been to such sweeping curtailment of their normal freedoms. The original advice to governments was to appeal to altruism in people and to keep emphasising the part people could play in the overall fight against the virus – and we have indeed seen this kind of messaging used by governments across the world on a daily, repeated basis. Support health workers, shield your elderly, protect your health service from collapsing, etc, etc. All are now common themes and it seems to have hit the mark with people. Suddenly national healthcare systems that were overlooked and underfunded have been promoted to centre stage and elevated to public hero status by the very governments that had starved them of money and stripped them back. It remains to be seen if the public will allow this neglect again in the aftermath. On top of this, the modern phenomena of mass media and the internet has spread stories and fear of this disease like no other in history. The collective panic has probably also led to this unprecedented outbreak of meek compliance with strict lockdown conditions.

There are also the economic aspects of lockdown. If you expect people to stay at home and not go to work you have to reassure them their wages are protected. To ask companies to suspend trade and deny them access to their customers, you have to protect businesses from cashflow crisis and collapse. Whilst the scientists were modelling the disease, Governments were frantically doing the maths of what finances would need to put in place in order to enact the measures and ensure compliance. Most decided to implement rescue packages the like of which has never been seen before. These decisions have upended decades of financial thinking and economic models.

On Friday evening, after one of the most extraordinary weeks in British history, a cabinet minister was among those trying to compute the scale of the government’s response to the coronavirus threat. In the end, he was forced to conclude: “We’ve just nationalised the economy” …….. As one minister put it, the question of “what the fuck happens after” is yet to be properly asked, never mind answered. “The economy will change. The nation will change. Our habits will change. But that’s for another day.” From mere advice to full lockdown: the week when it all changed 22 Mar 2020

With decades of payback ahead, it is said that young workers will bear the brunt throughout their working lives. Already disadvantaged, the generational divide in home ownership and financial security will be further exacerbated as they work through years of damaged economy and huge national debt. And to cap it all, we have some of the weakest leaders in recent history to guide a path through all these obstacles. Whilst most leaders worry and plan, Trump has become an irrelevance on the world stage and seems too busy rewriting the history of his response to the pandemic with an eye to the November election.

So here we are in lockdown, temporarily buffered from both the virus and the economic impacts of our forced inactivity. But what is becoming increasingly clear across the world is that there is no plan for the next stage. How do you get 2.6 billion people back out of lockdown. How does life return to normal when the virus still poses a threat, your populations are still fearful, and your economy is creaking under the weight? There is no blueprint for this and there is no other event in history that we can look to for clues.

Scientific report author Prof Neil Ferguson told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “We need to put in place an infrastructure, a command and control structure, a novel organisation. I’m reminded we had a department for Brexit in government. That was a major national emergency and we are faced with something even larger than Brexit. And yet I don’t quite see the evidence for that level of organisation”.

The public were told that a total lockdown at home would protect the bulk of us from the virus but would mean that we have no chance to be exposed and build immunity, meaning that when we emerge back into public we are all instantly at risk again.

They said vaccination would be the answer to this – then the reality emerged that vaccines take on average 10 years to develop, so the fast-track estimate of 18 months is aspirational, not something we can make firm plans on.

Then there was talk of an antibody test, which would allow testing to show which of us have unknowingly had the virus and are now immune – meaning we can safely return to work and life. For the past two months that been promised to be just a couple of weeks away, but so far no working test has materialised.

Public health scientists always recommended testing, tracking and isolating cases as the best way to deal with the virus. Countries like Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea who used these measures to quickly contain the outbreak before it could gain a foothold have had very different outcomes to countries, like the UK, who wasted those early weeks with inactivity. Testing, tracking and isolating is still the best strategy when coming out of lockdown, but many countries lack the infrastructure, laboratories and technicians to carry out the scale of testing that would be needed to undertake the task thoroughly enough. We failed to build this capacity because we didn’t fear pandemics in the same way that Asian countries did. Should those countries, who can successfully undertake testing and tracking, shut their borders to the countries who cannot contain the outbreak?

It’s clear no medical plan exists for how we can safely emerge from lockdown. Likewise, no hint of any economic plans for how the world will repay the financial buffering so many of us have received, nor any indication as to how the most disadvantaged are going to be protected from being the biggest losers in both the unemployment that will result from the lockdown as well as the cuts to public services that will inevitably happen during the financial recovery. The aftermath of a long period of enforced isolation, the stresses of lockdown, the interruption to education and the rise in domestic violence are all social consequences that need to be planned for and mitigations put in place.

After weeks of governments and institutions avoiding all questions and giving no hint as to when and how life can return to normality, finally over the last few days the first glimmers of thinking have been released. But these are mostly stating-the-bleeding-obvious type broad aims, without any clarification on how these aims can be achieved coming out of lockdown when they couldn’t be achieved on the way in.

You can’t replace lockdown with nothing

On 14th April the World Health Organization issued new guidance:

“You can’t replace lockdown with nothing,” Dr. Mike Ryan, executive director of WHO’s emergencies program, said at a recent briefing. Stressing the importance of a well-informed and committed population, he added, “We are going to have to change our behaviours for the foreseeable future.” “We don’t want to lurch from lockdown to nothing to lockdown to nothing,” Ryan said. “We need to have a much more stable exit strategy that allows us to move carefully and persistently away from lockdown.”

Any government that wants to start lifting restrictions must first meet six conditions:

- Disease transmission is under control

- Health systems are able to “detect, test, isolate and treat every case and trace every contact”

- Hot spot risks are minimized in vulnerable places, such as nursing homes

- Schools, workplaces and other essential places have established preventive measures

- The risk of importing new cases “can be managed”

- Communities are fully educated, engaged and empowered to live under a new normal

On 15th April the EU released its first guidance for exiting lockdown:

Efforts to flatten the curve of infections must have been successful.

Governments must ensure sufficient capacity in their national health care systems, not only regarding treatment capacities in hospitals but also in terms of sufficient medical supply stocks, including medicines, as well as the availability of care structures for vulnerable groups and discharged patients.

Countries should ensure they have the capacities for continued monitoring of the virus and for rolling out large-scale testing and contact-tracing to detect and control any potential new cases.

Action taken by national governments should be gradual and be done in coordination which each other, especially as regards the lifting of border controls between EU countries, a step which should only be taken once the situation of two bordering member states converges sufficiently.

Germany, Austria and Denmark appear to be the first to make tentative steps towards relaxing their lockdowns. We can only hope that this will provide some examples that others can learn from.

Meanwhile the IMF released a report on the predicted economic impacts, saying:

As a result of the pandemic, the global economy is projected to contract sharply by –3 percent in 2020, much worse than during the 2008–09 financial crisis. In a baseline scenario–which assumes that the pandemic fades in the second half of 2020 and containment efforts can be gradually unwound—the global economy is projected to grow by 5.8 percent in 2021 as economic activity normalizes, helped by policy support. The risks for even more severe outcomes, however, are substantial.

Predicting our way into this situation, predicting the course of the pandemic and predicting the number of deaths has proved easier than predicting how we get out of this place we have found ourselves.

In my previous reports I explored the science and looked at the modelling of the spread of the pandemic, searched the advice given to governments for estimates of deaths, duration of shut downs, etc. I looked at the social science reports and advice given to governments about how people cope with the stresses of quarantine. I read weekly Intensive/Critical Care hospital reports to track the health outcomes and look at which groups are most susceptible, which pre-existing illness are most dangerous, what medical interventions were most used, etc. All of this was available if you dug deep enough, I could track the scientists, academics and researchers as they shared their work and their data amongst themselves for peer review and their debates as they picked through the evidence they were basing their advice on.

But when it comes to lockdown exit strategy and when it comes to the long-term economics, I can find no pre-published papers being shared, no data to interpret, no niche discussion forums where debate is being had, no online university events I can gate-crash. Silence. Whatever planning and discussions happening must be going on behind firmly closed doors. Or more frighteningly, are not even happening perhaps, because there are no past studies to read and learn from, there is no raw data to interpret and there are no past examples to reanalyse. We are boldly going where no one has gone before. The biggest quarantine in human history happened piecemeal and it seems could end in the same haphazard way, as each country does its best to hobble together a plan for how to meet the future.

But it doesn’t have to be all doom and gloom. In a past report I mentioned that many of the studies of quarantined people told of the emotional stress, the impacts on mental health and the frequent symptoms of post traumatic stress that were observed. But there is a flip side to the phenomena of post traumatic stress – an outcome known as Post Traumatic Growth. This is defined as ‘positive psychological change experienced as a result of the struggle with highly challenging life circumstances”. Or put another way, it has been observed a person can come out of stressful situations and trauma realising they are more resilient than they thought and feeling more confidence in themselves. Also called Super-survivors, the conditions for this require remaining optimistic that things can be better, a belief you can take back personal control; strong social support and a sense of belonging is crucial for post traumatic growth.

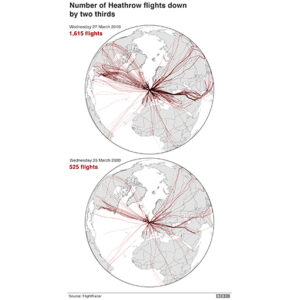

So, if we are living in a void where our leaders have made no future plans, we can choose to emerge from this crisis as Super-survivors. Now is the strongest chance in a lifetime for us to shape the future and demand changes. The climate has had a rest from human activity, the animals are venturing out into spaces that are normally monopolised by people and the oceans have had a short respite from the toxic waste we throw at it daily. The roads are silenced, the air is clear and the planes are grounded. We could choose how much destructive activity we wish to turn on again, or we can sleepwalk back into business as usual. Our economy has been halted and our institutions moribund – we can choose if we want a more just and fair distribution of wealth to built back up into its place. The importance of our healthcare, social care, essential services and key workers has been realised like never before – do we wish to celebrate these, reward them more in future and rebalance society.

The lack of any roadmap out of this mess means we have the chance to plan our own route. What we urgently need to lockdown is the blueprint for the rescue of our planet.

Hilary

References →

12:11